The Adolescent Brain: A brain in flux

Teenagers are wired to experiment with their environment and find their comfort zone amidst chaotic and tumultuous settings. They respond with raw emotional intellect to their surroundings and make new discoveries primarily because of the risks they are willing to take.

The species survives as a result of their daring and their insight. But what happens when things start to go wrong?

How can a young person turn it around? What can they depend on? Can they depend on science for answers? Do we make the science accessible to them?

The adolescent brain is a “brain in flux.”

Teens, or young adolescents, may find themselves confused by their inability to overcome a strong desire to experiment with multiple drugs or reckless sex. Teens may not realize that their behavior may be driven by a gene variant that causes a decrease in the amount of “dopamine” in the brain.

Dopamine is a chemical in the brain that makes us feel good. Scientists have called it part of the brain’s reward cascade. In other words, we feel good when this chemical is being produced in the brain. Certain drugs, types of food, and sex can also release dopamine into the brain, resulting in a similar cascade of good feelings.

This dopamine chemical cascade can be disrupted in individuals who have a dopamine genetic variant. The dopamine gene variant, has different characteristics, in some small way, from the normal gene that produces dopamine. However, even this small difference has the potential to alter the dopamine level and hence the gene’s function.

What does this mean from a practical point of view? Teenagers or adolescents that have the dopamine gene variant, may have less dopamine in their brain, which means it may take more stimuli such as drugs, alcohol or food, etc. to create the “good-feeling chemical- cascade.” For example, alcohol, cocaine, heroin, marijuana, nicotine, and glucose can all cause activation and neuronal release of the brain‘s chemical dopamine, which can then heal or fix the abnormal cravings (Wise and Rompre 1989).

Scientists have demonstrated this point in rats. They reproduced the dopamine gene variant in rats and showed the desperation with which the animals responded when offered a choice between cocaine and food. Scientists found that:

“Under certain circumstances rats who had the dopamine gene variant would forgo food to the point of starvation while working for brain stimulation or intravenous cocaine; presumably this is because the drug or stimulation can exert more powerful activation of central reward mechanisms than can peripheral rewards necessary for survival “ (Wise and Rompre 1989).

If you are a teen or an adolescent, it is important to pay attention to strong or overwhelming interest in drugs, food and sex because a dopamine gene variant may be driving this interest. Moreover, this gene variant may adversely influence your behavior and very much like the rat, your very survival may be called into question.

However, unlike the rat, a teen that is experiencing such feelings, may have an inner sense that something is awry but they may ignore their intuition and fail to get help for a variety of reasons. First, not being in control can create a sense of personal inadequacy that teens may feel responsible for. Second, teens may also feel that they are not measuring up to their peers in their ability to maintain control of their behavior. This can damage a teen’s sense of self-worth. Third, teens may worry that their behavior might disappoint parents and others who care about them so they don’t ask for help, lest they disappoint those who matter most.

A teen that is experiencing such feelings, may have an inner sense that something is awry but they may ignore their intuition and fail to get help for a variety of reasons.

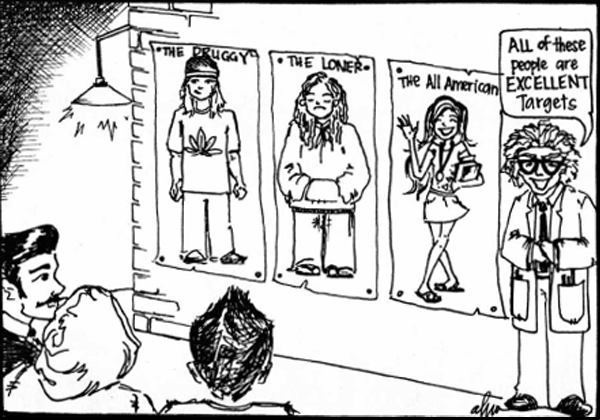

If you are a teen and any of these situations sound familiar, you need to stop and look at the options available for getting help. There are many reasons why you must take action. Not only is your well-being in danger, but you are in a vulnerable position where others may take advantage of you. Others may gain financially by your excess drug use and hence will not have your best interest in mind if they see that you are using poor judgment.

Furthermore, you are also in a vulnerable position from a physiological point of view if you are using drugs or alcohol. This is because the adolescent brain is a “brain in flux.”

Many areas of the brain undergo dramatic developmental changes in both structure and function during adolescence. Importantly, the brain regions, that are undergoing developmental changes are sensitive to alcohol and other drugs, and their function could be altered by these products.

It is also important to be aware of the time frame for the brain structural and functional changes that may suffer adversely by drug or alcohol use. Specifically, adolescence is defined by some researchers as the second decade of life, with ages up to 25 years considered late adolescence (Spear 2002).

At the same time, if you fear a dopamine gene variant may have already done too much damage to fix, you’re probably wrong. For example, the brain has a synaptic network in place that monitors the brain’s developmental changes and also provides redundant connections to the developing nervous system to influence its response to injury. So if your behavior has done damage, it is possible that the brain’s repair system is able to correct the damage.

A good example of this can be seen in the Boston Siamese cat. This cat has a “genetic variant” that has caused a misrouting of certain brain fibers (retinogeniculate) at a physical location in the brain called the “optic chiasm.” The phenotype, or the physical expression of this gene variant, can be seen in the cat’s “crossed eyes.” In this cat’s brain, due to this gene variant, one might expect to see fewer synaptic connections.

(Synapses are the neurons that transfer chemical and electrical messages throughout the brain.)*

However, incredibly, overproduction of synapses during the cat’s development period (perhaps synonymous to human adolescence), provides a safety net whereby a higher level of available synapses, allows the cat brain to create an unusual set of connections that transmit communication from one brain hemisphere to the other (Shatz 1977). The compensation for the genetic mistake will lead to persistence of the synaptic connections throughout the cat’s life.

Teens should know that similar synaptic damage control networks are working for their benefit during adolescence. Nonetheless, teens should not overtax the brain’s damage control systems.

Teens who might be worried that they may have the dopamine gene variant should also know that sometimes gene variants can have benefits. For example, individuals with the dopamine gene variant described in this article, also have been found to have a higher IQ score on certain intelligence tests (Tsai et al. 2002) (Antolin et al. 2009).

Teens who might be worried that they may have the dopamine gene variant should also know that sometimes gene variants can have benefits.

If you are someone that is interested in participating in studies that scientists might conduct to learn more about the dopamine gene variant, let us know and DNAScribe will contact you to let you know about any available or forthcoming studies. The studies will be examining what types of environmental factors act in combination with the dopamine gene variant to contribute to its potential effect and how these effects can be prevented by diet or other forms of intervention.

Contact us at: dnascribestory@optimum.net

Glossary:

*Synapses: Chemical synapses are specialized junctions through which neurons signal to each other and to non-neuronal cells such as those in muscles.

References:

-

Antolin, T., S. M. Berman, B. T. Conner, T. Z. Ozkaragoz, C. L. Sheen, T. L. Ritchie & E. P. Noble (2009) D2 dopamine receptor (DRD2) gene, P300, and personality in children of alcoholics. Psychiatry Research. 166, 91-101.

-

Shatz, C. J. (1977) Anatomy of interhemispheric connections in the visual system of Boston Siamese and ordinary cats. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 173, 497-518.

-

Spear, L. P. (2002) Alcohol’s effects on adolescents. Alcohol Research Health, 26, 287-291.

-

Tsai, S.-J., W.-Y. Y. Younger, C.-H. Lin, T.-J. Chen, S.-P. Chen & C.-J. Hong (2002) Dopamine D2 receptor and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor 2B subunit genetic variants and intelligence. Neuropsycholobiology, 45, 128-130.

-

Wise, R. & P. Rompre (1989) Brain dopamine and reward. Annual Review of Psychology, 40, 191-225.